En palabras de Beatriz Colomina, las mujeres son los fantasmas de la arquitectura, presentes en todas partes, cruciales, pero extrañamente invisibles. Hasta hace pocos años atrás la contribución femenina en el medio pasaba prácticamente inadvertida, muchas arquitectas formaban parte de distinguidos estudios y eran autoras de importantes obras, sin embargo no fueron lo suficientemente reconocidas. Ejemplo de esto es lo que ocurre en 1991, cuando no se consideró a Denise Scott Brown en el Pritzker concedido a Robert Venturi, a pesar de que las obras habían sido proyectadas en conjunto y además situándose en un momento en el cual las arquitectas se encontraban activamente aportando a la disciplina. Muchos recién cayeron en cuenta de la presencia femenina cuando el premio Pritzker, que se entrega desde 1979, fue

entregado por primera vez a una mujer, Zaha Hadid, en el 2004.

In the words of Beatriz Colomina, women are the ghosts of modern architecture, present everywhere, crucial, but strangely invisible. Up until a few years ago, feminine contribution on the field went by practically unnoticed, several female architects were part of distinguished studios and were authors of important pieces, and nonetheless they weren’t recognized enough. An example of this is what happened in 1991, Denise Scott Brown wasn’t considered for the Pritzker price granted to Robert Venturi, despite of the fact that the projects had been designed together and also in a moment in which women architects were active and contribuing to the field. Many started realizing of the female presence when the Pritzker price, which has been granted since 1979, went for the very first time to a woman, a woman named Zaha Hadid in 2004.

" No tener referentes femeninas es un problema. Hace muchos años que hay mujeres ejerciendo arquitectura, haciendo cosas importantes, y que si no las visibilizamos y somos conscientes de ello, siempre estaremos empezando” (1)

- Zaida Muxi

“(…) Not having female referents is a problem. Women have been exercising architecture for years, doing interesting and important things, and if we don’t make them visible and if we don’t make ourselves conscious about it, then we will always just be in the starting point. (…)”

En las últimas décadas, se ha incrementado la presencia de arquitectas en eventos y galardones internacionales, siendo reconocidas por el medio disciplinar, y teniendo una vasta participación en importantes tribunas de la arquitectura contemporánea. Una de las iniciativas destacables es la del blog Un día I Una arquitecta, el cual publica a diario biografías de arquitectas de todo el mundo. Inés Moisset (una de las gestoras de la iniciativa) cuenta que al comienzo del proyecto se les preguntaba si habrían suficientes nombres de arquitectas. Sin embargo, al segundo año los contenidos crecieron considerablemente, teniendo que elaborar una segunda edición. Un día | una arquitecta, logró construir un relato que interpone el aporte femenino en la historia de la arquitectura.

Otra clara muestra de ello, es el auge de arquitectas en la vigente exposición internacional de arquitectura La Biennale di Venezia, que este año contó con una gran presencia femenina latinoamericana dentro de los participantes, y donde además las curadoras del espacio principal “Freespace” fueron las arquitectas Yvonne Farrell y Shelley McNamara.

El tema central de este año “Freespace”, que se lleva a cabo en el Arsenale de Venecia, propone según las curadoras de la muestra, un “regalo de espacio libre adicional a los habitantes”, “aquello que es inesperado en cada proyecto”, “la oportunidad de un espacio democrático no programado para usos no concebidos”. Sugiriendo una mirada sensible sobre aquellos espacios cotidianos que se transforman en arquitectura.

On the latest decades, the presence of female architects on international events and awards has increased, being recognized by the disciplinary medium, and having a vast participation in the important grandstands of contemporary architecture. One of the remarkable initiatives is the one of the blog Un dia I Una arquitecta, who publish the biography of architects from around the world. Inés Moisset (one of the creators of the initiative) says that in the beginning she asked herself if there would be enough female architects, suspecting there wouldn’t be enough women to talk about. By the second year the contents of the page increased considerably, having to elaborate a second edition. Un dia I Una arquitecta, was able to build a story that managed to interpose the female contribution to the history of architecture.

A clear example of this, is the increase of female architects participating in the recent version of the internationally recognized exposition of the Venice Architecture Biennale, where this year the presence of Latin American architects is at its strongest yet and where the curators of the main space “Freespace” were the female architects Yvonne Farrell y Shelley McNamara.

The main theme of this year “Freespace”, that takes place in the Venice Arsenale, proposes according to the exposition’s curators, a “gift of additional free space for the inhabitants”, “that of what is unexpected of each project”, “the opportunity of a democratic space, non-programed for unconceived usages”. Emerging a sensitive view about those day-to-day spaces that transform themselves into architecture.

“Más que una mirada masculina o femenina, creo en la necesidad de incorporar una perspectiva de género al proyecto arquitectónico y urbano. Es necesario pensar las ciudades y los edificios de un modo inclusivo y equitativo (2)”

"More than a masculine or feminine view, I believe on the necessity of incorporating gender perspective to the architectural and urban project. it is necessary to think cities and buildings with terms of inclusivity and equality"

El primer grupo de arquitectas que presentaremos, exponen parte de su trabajo en la actual Bienal de Venecia. Todas responden de forma coherente con el tema propuesto, ya que si algo tienen en común es su mirada crítica, social y consciente de la arquitectura. En sus obras se puede percibir el trasfondo al momento de proyectar, partiendo siempre del lugar y las necesidades particulares, ofreciendo una arquitectura sensitiva, local, y al mismo tiempo sustancial.

Una mexicana, una chilena y una brasileña, son parte de una flamante generación de nuevas referentes de las que hay que hablar.

We will present the first group of women, that are now presenting their work no the most recent Venice biennale. They all coherently respond with the proposed theme, because if there is one thing they have in common is their critical, social and conscious view of architecture. In their work we can perceive the background meaning whenever is time to design, always starting from the place and specific necessities, offering a sensitive, local and at the same time substantial architecture.

A Mexican, a Chilean and a Brazilian architect are part of a starling new generation of referents who must be talked about.

Rozana Montiel, México. “Stand Ground” BV2018

“Toda arquitectura es política. Podemos leer en los espacios cotidianos las prioridades políticas de nuestra sociedad. La arquitectura tiene el poder de dar forma al comportamiento cívico porque establece los principios fundadores de los intercambios públicos y sociales". (3)

- Rozana Montiel

“All architecture is political. We can read in common spaces the political priorities of our society. Architecture has the power of shaping civic behavior because it establishes the founding principles of public and social exchange.”

Mexican architect, founder of the Rozana Montiel Estudio, who works in architectural design, art and urbanism. She has a degree in Architecture and Urban Planning from the Ibero-American University. Mexico (1998). Complemented her education with a Master’s degree in Architectural Theory and Criticism in the Universitat Politécnica de Catalunya, Spain (2000).

She has participated on five editions of the Venice Architecture Biennale. She has also participated on two editions of the Rotterdam Biennale, the Sao Paulo Biennale and the Lima Biennale. Among her most recognized projects we can find: Void Temple, Highway Modules, Patinadores House, METRO-polis, COURT and Common-unity, among others.

The action field of her work is quite diverse and her proposals try to generate multiple narratives that propose specific and coherent speeches for each project. Part of her most remarkable work is centered on projects of urban rehabilitation on vulnerable areas of Mexico.

Arquitecta mexicana, fundadora de Rozana Montiel Estudio, trabaja en diseño arquitectónico, arte y urbanismo. Es licenciada en Arquitectura y Planeación Urbana por la Universidad Iberoamericana, México (1998). Complementó su formación con el Máster en Teoría y Crítica Arquitectónica por la Universitat Politécnica de Catalunya, España (2000).

Ha participado en cinco ediciones de la Bienal de Arquitectura de Venecia. También ha participado en dos ediciones de la Bienal de Rotterdam y en las bienales de Sao Paulo y Lima. Dentro de sus proyectos más reconocidos encontramos: Vacío circular, Módulos carreteros, Casa Patinadores, Metro-polis, Cancha y Común-Unidad, entre otros.

El campo de acción de su trabajo es muy diverso y sus propuestas buscan generar múltiples narrativas que propongan discursos coherentes y específicos para cada proyecto. Parte de su obra destacada se centra en proyectos de rehabilitación urbana en zonas sensibles de México.

1. Estudio Rozana Montiel

Montiel got awarded with several scholarships between 2001 and 2003 like the FONCA scholarship (2010 and 2013) and the Holocim Foundation scholarship (2007), she also won several awards such as the Awards for Emerging Architecture (London) for “Void Temple” (2014), the silver medal on the second CDMX Biennale in the category of public space rehabilitation (2015), the Emerging Voices (2016) price for The Architectural League of New York and the Moira Gemmill Prize for Emerging Architecture (2017) in the Premios Women in Architecture awards, announced by the Architectural Review with The Architects Journal.

Montiel se adjudicó diversas becas entre los años 2001 y 2013 como la Beca del FONCA (2010 y 2013) y la beca de la Fundación Holcim (2007), además de ganar varios premios como el premio Awards for Emerging Architecture (Londres) por el proyecto “Vacío Circular”(2014), la medalla de plata en la 2da Bienal de CDMX en la categoría de rehabilitación de espacio público (2015), el premio Emerging Voices 2016 por The Architectural League de Nueva York y el Moira Gemmill Prize for Emerging Architecture 2017 en los Premios Women in Architecture, anunciado por Architectural Review junto a The Architects Journal.

“Buscamos el contenido de nuestra arquitectura en el contexto mismo; el paisaje se convierte en programa (…) resignificamos el uso de materiales sencillos. Pero sobre todo creemos que la belleza es un derecho básico: el buen diseño es posible para todos si hay un uso virtuoso de recursos”. (4)

- Rozana Montiel

"We look for the content of our architecture on the context its self; the landscape turns into the program (...) give new meaning to the use of simple materials. But above all we believe on the beauty of basic rights; good design is possible for everyone if the use of resources is virtuous”

2 y 3. Vacío Circular / Cancha – Rozana Montiel | © Iwaan Baan - Sandra Pereznieto

This year Rozana Montiel was the only Mexican studio invited by the curators of the 16th Venice Biennale International exhibition to participate along 71 projects from around the world in the “Freespace”

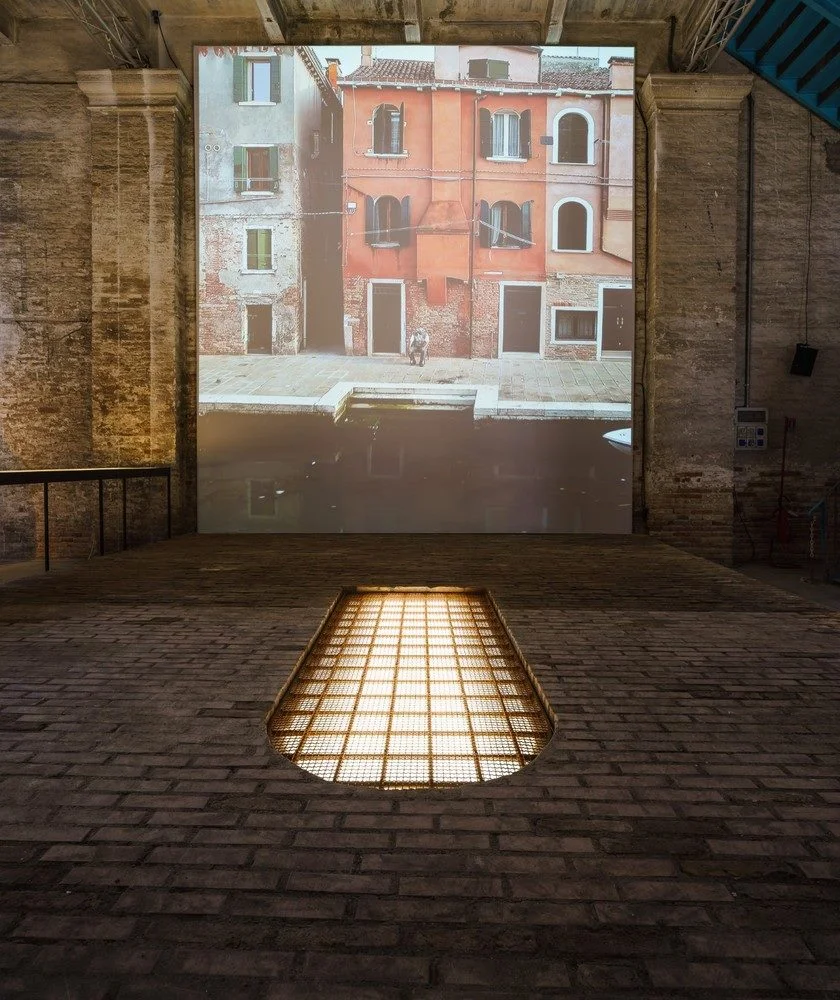

The Mexican studio’s proposal titled “Stand Ground” explores the theme of “Freespace” as an imperative to take action and a social resource of free will (6). Her intervention offers to the onlookers a different experience of space based on what is fictitious and poetic. Transforming the wall into a floor that virtually connects the exterior with the interior, transforming a barrier into a horizon. The building’s space opens up to the streets through a live projection of the Venice Canals on a screen placed in front of the back wall of the exhibition. This way the exterior is introduced to the interior space of the exhibition so that the visitors can get involved with a different comprehension of space.

Este año, Rozana Montiel fue el único estudio mexicano invitado por las curadoras de la 16° muestra Internacional de la Bienal de Venecia a participar junto a 71 proyectos de todo el mundo en el “Freespace".

La propuesta del estudio mexicano titulada “Stand Ground” (Sostener terreno/Defender una postura) explora el tema del “Freespace” como un imperativo para actuar y un recurso social de libre acción. Su intervención ofrece a los visitantes una experiencia diferente del espacio basada en lo ficticio y lo poético. Transformando el muro en un piso que conecta virtualmente el exterior con el interior, convirtiendo una barrera en horizonte. El espacio del edificio se abre a las calles, a través de una proyección en tiempo real del canal de Venecia en una pantalla colocada frente al muro posterior de la exhibición. De esta manera, se introduce el exterior dentro del espacio de exhibición y los visitantes se involucran sensorialmente en la comprensión del espacio.

4. “Stand Ground” - Estudio Rozana Montiel | © Estudio Rozana Montiel y Sandra Pereznieto.

The result, a 1:1 reproduction of the Arsenale wall made of Venetian brick, paving the exhibition floor to create a new border. Visitors can not only walk and inhabit the wall, rebuild on its horizontal position, but they are also aware of its weight and constructive technique.

El resultado, una reproducción 1:1 del muro del Arsenale hecho de ladrillo veneciano, pavimentando el piso de la exhibición para crear un nuevo borde. Los visitantes no sólo pueden caminar y habitar el muro, reconstruido en su posición horizontal, sino que además pueden ser conscientes de su peso y su método constructivo.

"(…) Introducimos la calle en un espacio amurallado, abrimos espacios privados a la esfera pública, re-significamos un muro como un piso, transmutamos una barrera en un territorio. (…) el uso conceptual del espacio es intrínseco a su experiencia. " (5)

- Rozana Montiel

"(…) We introduced on the street a walled space, opened private spaces to the public sphere, re signified a wall as floor, and transmuted a barrier into territory. (…) conceptual usage of space is essential to its experience"

The installation is complemented with tables that show montages of the studio’s design process, their methodology and investigation as well as the intervention of public space in the housing units related to the installation. The book HU: Common spaces in Housing units, was presented a compilation about public space rehabilitation projects.

La instalación se complementa con mesas que exhiben montajes con el proceso de diseño del estudio, su metodología e investigación. Así como las intervenciones del espacio público en unidades habitacionales relacionadas con la instalación. Donde se presenta el libro UH: Espacios Comunes en Unidades Habitacionales, una compilación de proyectos sobre rehabilitación de espacio público.

5 y 6. UH - Estudio Rozana Montiel | © Estudio Rozana Montiel y Sandra Pereznieto.

“A través de los espacios que diseñamos los arquitectos, potenciamos distintas relaciones humanas que trascienden incluso la problemática de género (…) falta re-pensar al “usuario estándar” para el cual se hace arquitectura”(6)

- Rozana Montiel

"Through spaces designed by architects, we promote human alternatives that transcend even the gender problematic (...) we need to re-think about the "standard user" for whom architecture is designed"

Alejandra Celedón, Chile. “Stadium” BV2018

“(…) las plantas, a pesar de estar pensando un edificio, también empiezan a dibujar un proyecto de ciudad, empiezan a develar y desenvolver temas que afecten el territorio urbano. La arquitectura, no como un objeto en sí mismo, sino la arquitectura como una pieza urbana”(7)

- Alejandra Celedón

"the plans, despite of being thought as buildings, it also starts to trace a city plan, reaviling and deploying issues that affect the urban territory. Architecture, not as an object in itself, but architecture as an urban piece"

Arquitecta graduada de la Universidad de Chile (2003) y magíster en Estudios de Arquitectura Avanzada en Bartlett University College, London (2007). Doctora en Historia y Teoría de la Arquitectura por la Architectural Association School of Architecture, London. Su tesis doctoral “Rhetorics of the Plan” (becada por Becas Chile 2014) estudia la relación entre los dibujos y las palabras, entre los objetos y los discursos, discutiendo cómo el inestable significado de la planta a través del tiempo ha registrado y detonado cambios disciplinares.

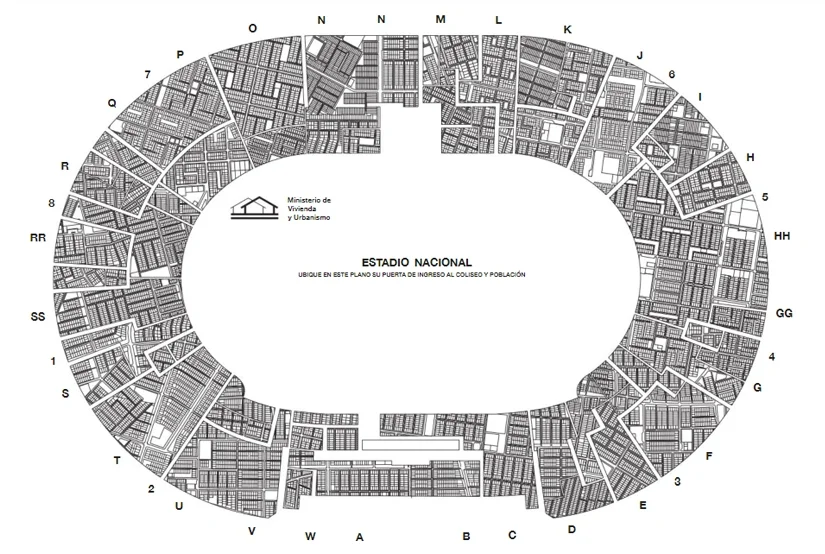

Actualmente, la arquitecta fue escogida curadora de La exposición Stadium en la Bienal de Venecia. Donde plantea un pabellón cargado de historia y simbolismos, que superpone una ciudad, un edificio, y un evento en una suerte de cartografía que devuelve la imagen segregada de la ciudad de Santiago. La propuesta fue seleccionada por un jurado compuesto por figuras como Smijlan Radic, Edward Rojas, Eva Franch y Enrique Walker, entre otros.

La exposición busca que los elementos –frágiles y pesados a la vez– cuenten la historia del momento en que los ciudadanos “sin casa” pasan a ser propietarios por primera vez, a modo de "fragmentos simbólicos de esta transmutación".

El pabellón, se enmarca dentro de una investigación más amplia sobre retóricas y políticas de vivienda en los ochenta en Chile, que ha tomado distintas formas, desde cursos a talleres de investigación, artículos y presentaciones en congresos.(8)

Architect graduated from Universidad de Chile (2003) with a Master’s degree in Advanced Architecture Studies from Bartlett University College, London (2007). A PhD in History and theory of Architecture from the Architectural Association School of Architecture, London. Her PhD thesis “Rhetorics of the Plan” studies the relationship between drawings and words, between objects and speeches, discussing how the unstable meaning of the floor plan, through time, has sparked and registered changes on the discipline.

Recently, she was chosen as the curator of the Stadium exposition in the Venice Biennale. It poses a pavilion loaded with history and symbolism, which superimposes a city, unity, and an event in a kind of cartography that returns the segregated image of the city of Santiago. The proposal was selected by a jury with figures like Smilan Radic, Edward Rojas, Eva Franch y Enrique Walker, among others.

The exposition, curated by Alejandra Celedón, looks for the elements –fragile and heavy at the same time- to tell the history of the moment where the “homeless” citizens happen end up being, for the very first time, owners, through “symbolic fragments of this transmutation”.

The pavilion, is framed in a more ample investigation about the eighties Chilean housing rhetoric and politics, that has taken different shapes, from courses to investigation workshops, articles and congress presentations. (8)

7. Stadium – Alejandra Celedón | © Cristóbal Palma

Celedón cuenta que la planta que da origen tanto al concepto curatorial como al diseño del pabellón, la encontró un ex ayudante de investigación (Eneritz Hernández) quien pensó que le interesaría y le avisó de inmediato. Expresando: “Apenas recibí la foto del plano entendí que teníamos entre manos un objeto y una imagen muy potente, testigo tanto de nuestra historia como de nuestra ciudad presente.”

Celedón says that the plant that gives rise to both the curatorial concept and the design of the pavilion was found by a former research assistant (Eneritz Hernández) who thought he would be interested and immediately notified him. Expressing: "As soon as I received the image of the floor plan I understood that we had in our hands a very powerful object and image, witness of both our history and our present city"

8. Planta Stadium

“Stadium”, a reflection about local housing politics, based on a day, the 29th of September 1979, where Chile’s National Stadium turned into building and city simultaneously for one day, the building was occupied by 40.000 families (250.000 people) coming from all places of Santiago, for a massive operative that provided property titles for the settlers, regularizing decades of improvised land occupation. A plan of the stadium was prepared with the limits of each neighborhood instead of bleachers, transforming the genesis of the current layout of Santiago into a building’s plan. From sporting venues and religious gatherings to a prison camp, the exposition recreates the different functions as if it were a machine to visit and revisit the stadium’s typology. This is the story told through a drawing of past events that foreshadowed the city’s future inside of a building structure. The exposition tells a double story intertwined in a single drawing: the one of a building (through its different usages) and the one of a city (through its housing development), both converging into one. (9)

“Stadium”, basado en el día 29 de septiembre de 1979, donde el Estadio Nacional de Chile fue un edificio y una ciudad por un día, el edificio fue ocupado por 40.000 familias (250.000 personas) de toda la ciudad de Santiago, para un operativo masivo que proporcionó títulos de propiedad a los pobladores, regularizando décadas de ocupación improvisada de tierras. Se preparó un plano del Estadio con el contorno de barrios en lugar de gradas, convirtiendo la génesis del trazado actual de Santiago en el dibujo de un edificio. Desde eventos deportivos y eventos religiosos a un campo de reclusión, la exposición recrea las diferentes funciones como una máquina para ver y revisitar la tipología del estadio. Esta es la historia contada a través de un dibujo de un evento del pasado, que previó el presente de una ciudad dentro de un edificio. La exposición narra una doble historia entrelazada en un dibujo: el de un edificio (con sus usos diferentes) y el de una ciudad (con su desarrollo de vivienda), ambos convergiendo en uno solo. (9)

9. Stadium – Alejandra Celedón | © Laurian Ghinitoiu

Una gran maqueta del edificio hecha de tierra apisonada se ubica al centro de la sala, y al examinar detalladamente, la estructura devela una serie de capas y segmentos que revelan una ciudad con un crecimiento no planificado. Las sesenta piezas que componen la forma ovalada del edificio ya no parecen hechas de tierra, sino más bien talladas en ella. Las distintas capas con ligeras variaciones de color y textura recuerdan que es el suelo lo que está en juego en el Pabellón de Chile.

A great scale model of the building made of rammed earth is placed in the middle of the room, and when examined in detail, the structure unveils a series of layers and segments that reveals a city with unplanned growth. The sixty pieces that make up the oval shape of the structure don´t look as if they were made of soil, but rather carved on the surface. The different layers with light variations of color and texture remind us that it is soil what’s on stake in Chile’s Pavilion.

10. Stadium – Alejandra Celedón | © Gonzálo Puga

A critic representation of the stadium’s plan as a building that represents the urban imagery is what was presented. The pavilion is articulated in four momentums: the Event Hall, The Islands, The Horizon and The City. The first of them is dedicated to the investigation of archives and findings surrounding the event; The Islands amplify the information through screens with interviews of people that where present on the stadium’s event; The Horizon is dedicated to de multiple functions that the stadium has had; The city is represented on the background wall, which contains a representation of Santiago that reveals the distance between the Stadium and the settlings, with the building as a witness of the unequal development of the city.

Se presenta una reconstrucción crítica de la planta del Estadio como un edificio que representa la imagen urbana. El pabellón se articula en cuatro momentos: la Sala de Eventos, Las Islas, El Horizonte y La Ciudad. El primero está dedicado a la investigación de los archivos y a los hallazgos que rodean el evento; Las Islas amplifican la información a través de pantallas con entrevistas a personas presentes en el evento del Estadio; El Horizonte está dedicado a las múltiples funciones que ha albergado el Estadio, a través de un video basado en archivos; La Ciudad, se representa en el muro del fondo, el cual contiene una representación de Santiago que revela la distancia entre el Estadio y las poblaciones, con el edificio como testigo del desarrollo desigual de la ciudad.

Carla Juacaba, Brasil. Capilla para el vaticano BV2018

“El aspecto más importante que debe abordarse es el contexto en el que se está proyectando: el medio ambiente, el clima, la luz natural, posibilitan aprovechar todo su potencial, que deriva en uso de materiales locales”. (10)

- Carla Juaçaba

“(…) the most important aspect that should be addressed is the context on which is being projected; environment, climate and natural sun light, make it possible to take advantage of their full potential, that can leeway in the usage of local materials

Carla Juacaba estudió arquitectura en la Universidad Santa Úrsula, Rio de Janeiro. Egresó como arquitecta en 1999. Desde el 2000, desarrolla su práctica profesional en arquitectura e investigación de manera independiente desde su oficina en Río de Janeiro. Fue Jurado de BIAU Bienal Iberoamericana Cádiz, España, 2012 y en 2013 ganó la primera edición del premio internacional ArcVision Mujer y Arquitectura, un premio internacional para la arquitectura social de las mujeres establecidos por Italcementi Group.

Entre sus obras encontramos la Casa Rio Bonito (2005); la Casa Varanda (2007); la Casa Mínima (2008); la Casa Santa Teresa (2012) y el Pabellón Humanidade 2012, que diseñó junto a la escenógrafa Bia Lessa cuando los arquitectos Ariadna Cantis y Andrés Jaque la incluyeron en Freshlatino02, una exposición patrocinada por el Instituto Cervantes.

Carla Juacaba studied architecture in Santa Úrsula University, Rio de Janeiro. She graduated as an architect on 1999. Since 2000, she develops her professional practice in architecture and investigation independently from her office in Rio. She was a jury of the BIAU, Ibero American Biennale, in Madrid, Spain (2012) and in 2013 she won the first edition of the price of ArcVision Mujer y Arquitectura, an international social architecture award for women, established by Italcementi Group.

Amongst her work we can find Rio Bonito house (2005); Varanda house (2007); Minima house (2008); Santa Teresa house (2012) and the 2012 Humanidade, that was designed with scenographer Bia Lessa when architects Ariadna Cantis and Andrés Jaque included her for Freshlatino02, an exposition patronized by the Cervantes Institute.

11 y 12. Casa en Santa Teresa - Carla Juacaba | © Federico Cairoli.

Este año, la 16° Bienal de Arquitectura de Venecia marca el debut de El Vaticano con una exhibición que reúne a 10 arquitectos, los cuales diseñaron capillas que serán relocalizadas en distintos puntos alrededor del mundo, una vez que el evento finalice. Emplazadas en un bosque en la isla veneciana de San Giorgio Maggiore, estas construcciones se inspiran en la Capilla del Cementerio del Bosque en Estocolmo, obra del sueco Erik Gunnar Asplund finalizada en 1920. Las capillas han sido diseñadas por reconocidos arquitectos como Norman Foster, Eduardo Souto de Moura y Smiljan Radic, entre otros.

This year, the 16th Venice architectural biennale marks the debut of The Vatican with an exhibition that gathers 10 architects, who designed chapels that would be placed on different points around the world, eleven the event has finalized. Located in a forest in the Venetian Island of San Giorgio Maggiore. These constructions are inspired by The Woodland Cementary Chapel, in Stockholm, work designed by the Swedish architect Erik Gunnar Asplund, finalized in 1920. Each chapel has been designed by recognized architects such as Norman Foster, Eduardo Souto de Moura and Smiljan Radic, among others.

13. Vista Superior - © Laurian Ghinitoiu

La capilla diseñada por Juaçaba busca una "integración armónica" entre los árboles y las aguas que rodean a Venecia, delineando el espacio interior de la capilla con la vegetación cercana. Asimismo, el espacio entre las copas de los árboles, que deja entrever el cielo, funciona como cubierta de la capilla.

Estructuralmente, la capilla está formada por cuatro vigas de sección cuadrada: una cruz de pie y otra proyectada en el suelo. Una de ellas sirve como asiento, y la otra como hito silencioso. El conjunto se construye sobre durmientes de hormigón a cada metro, dando ritmo al sistema; mientras que las vigas son de acero inoxidable pulido, transformándose en espejos que reflejan el entorno. Así, la capilla puede "desaparecer" en ciertos momentos, dependiendo del reflejo del sol y los árboles.

Juacaba’s chapel looks for a “harmonic integration” between the trees and the water that surrounds Venice, tracing the internal space of the chapel with the nearby vegetation. Likewise, the space in-between trees that shows a glimpse of the sky, works as the chapel’s cover.

Structurally, the chapel is made of four cross section beams: a standing cross and a cross projected on the floor. One of them works as a bench, and the other one as a silent landmark. The set is built over concrete sleepers placed every one meter, giving to the system rhythm; while the beams are of polished stainless steel, that transform into mirrors that reflect the surroundings. Like that, the chapel can “disappear” at certain points, depending on the reflection of the sun and trees.

14. Capilla para el Vaticano - Carla Juacaba | © Alessandra Chemollo

15. Capilla para el Vaticano - Carla Juacaba | © Nadia Shira Cohe para Clarín, New York Times.

“Referir a las mujeres arquitectas es un tema complejo; no sólo porque es una profesión aún muy masculina y debemos imponer mucho para ganar espacios. No hay ninguna diferencia entre el trabajo de los hombres y la de las mujeres (...) Es fácil hablar de la igualdad entre los sexos, pero la realidad muestra que todavía hay un largo camino por recorrer" (12)

- Carla Juacaba

“Referring to female architects is a complex theme, not only because it’s a profession that is still very masculine and we have to impose ourselves quite strongly in order to gain spaces. There is no difference between the work of men and women (…) It’s easy to talk about equality of sexes, but reality shows us that there is still a long way to go.”

La recopilación de estas referentes en la arquitectura contemporánea deja en evidencia el posicionamiento femenino en el medio como un hecho concreto y visible. No hace falta de-mostrar, sino más bien destapar lo que hacen y llevan haciendo hace años las mujeres en arquitectura y urbanismo.

El ímpetu y la mirada femenina, han aportado análisis e impulsado interrogantes al debate sobre la arquitectura-urbanismo y género. ¿Existe la arquitectura de género?; ¿La historia de la arquitectura ha segregado los espacios sin tener consciencia de género?; ¿Por qué, para qué y cómo aplicar la perspectiva de género al diseño arquitectónico y urbano?; Cómo se aplica la perspectiva de género en la arquitectura?

The compilation of these female referents in contemporary architecture evidences the presence of women in the medium as visible and solid fact. It’s not necessary to demonstrate, but rather uncover what they do and have been doing for years in architecture and urbanism.

The impetus and female approach, have contributed to the analysis and have boosted questionings to the debate about architecture-urbanism and gender. Is gender architecture real?; Has the history of architecture segregated spaces without being conscious of gender?; Why, for what and how can we apply gender perspective to the architectonic and urban design process?; How is gender perspective applied in architecture?

“No existe un ciudadano tipo para quien diseñar el espacio público sino una ciudadanía plural y compleja con quien consensuar el diseño del espacio privado y del espacio colectivo. Se trata de construir una cultura de diálogo en el intento de establecer una vida más humana para cada necesidad (13)”

“There is no citizen type for whom to design public spaces, but rather a plural and complex society with whom the design of public and collective space can be agreed upon. It is about constructing dialogue culture in the attempt of establishing a more human life for each necessity”

Al hablar de género en arquitectura no debemos entender el concepto como un rol asignado asociado a un determinado sistema de valores socioculturales o ideológicos "La aplicación de la perspectiva de género en la arquitectura comienza desde el programa, que debe dar respuesta a necesidades concretas y tener en cuenta que no hay un usuario universal neutro ni respuestas absolutas, hay que considerar todas las variables y tomar decisiones coherentes con la realidad". Se trata de construir un sistema de valores que reconozca las desigualdades, que rompa los dogmas, teniendo consciencia de las diferencias. Hacer arquitectura, construir ciudad, responde de forma inherente a diversas necesidades, y no concibe responder solo a algunas. Es necesario pensar las ciudades y los edificios de un modo inclusivo y equitativo.

When talking about gender in architecture we shouldn’t understand the concept as a roll designated to a determined sociocultural or ideological values system The application of gender perspective starts from the program, which shall give an answer to concrete necessities and keep in mind that there is now universal neutral user nor absolute answers, we have to consider every variable and take decisions that are coherent with reality.(16) It’s about building a system of values that recognizes inequalities, that tears dogmas, always conscious about differences. Making architecture, building cities, responds inherently to a diversity of necessities, and does not conceive answering to just a few. It is necessary to think cities and buildings through an inclusive and equal way.

“Hombres y mujeres no hacen arquitectura diferente, ni una mejor que la otra. Perciben de manera distinta el espacio y su entorno y eso impacta la producción arquitectónica”.(14)

- Zaida Muxi

“Men and women don’t make different architecture, one is not better than the other. They perceive space and it’s environment differently and that impacts on architectonic production”

FABIOLA PINEDA ZENTENO

Traducción Isabel San Martín

REFERENCIAS:

(1) MUXI, Zaida. Entrevista “pensar las ciudades con mirada de género”. Revista Sophia, 29 Septiembre 2017.

(2) QUIROGA, Carolina. Articulo “Mujeres en obra: la hora de la reivindicación para las arquitectas argentinas” por Carolina Muzi. Revista Infobae, Argentina, 25 de abril de 2018

(3) MONTIEL, Rozana. Articulo “Ganadoras de los Premios ‘Women in Architecture’ 2017” Revista ArchDaily, 3 Marzo 2017

(4) MONTIEL, Rozana. Entrevista a Rozana Montiel por Plataforma Arquitectura, 15 Mayo 2018

(5) MONTIEL, Rozana. Descripción memoria oficial página web Estudio Rozana Montiel http://rozanamontiel.com

(6) MONTIEL, Rozana. Entrevista por Glocal Design Magazine sobre el papel de la mujer en la práctica contemporánea, 08 Marzo 2017.arquitectónica

(7) CELEDÓN, Alejandra. “PLANTA PLANO PLAN: Entrevista a Alejandra Celedón”.Revista REVISTARQUIS (Universidad de Costa Rica) Vol 2-2014. Numero 6.

(8) ARQUINE. Stadium el pabellón chileno para Venecia, 9 noviembre, 2017.

(9) CELEDON, Alejandra. Memoria oficial. Página web http://stadium-pavilion.cl

(10) JUACABA, Carla. Articulo la consideracion del contexto en la arquitectura de Brasil. Revista Platafroma Arquitectura, 16 Enero 2018

(11) CANTIS,Ariadna. Articulo “Frescura Latinoamericana”. Diario El Pais, España, 30 Marzo 2013

(12) JUACABA, Carla. Articulo Carla Juacaba. Blog Un dia | Una Arquitecta. 06 Febrero 2016

(13) NOVAS,Maria.Articulo Arquitectura y Género. Revista ENLACE arquitectura

(14) MUXI, Zaida. Entrevista a Zaida Muxi para Revista “Su Casa” No.46, Costa Rica,2008.

LINKS

https://dostercios.cl/entrevista/alejandra-celedon-stadium

https://undiaunaarquitecta.wordpress.com

http://www.federicocairoli.com

http://rozanamontiel.com

http://www.carlajuacaba.com.br

http://www.serpentinegalleries.org

http://www.labiennale.org